How to Live Together

ST Paul St Gallery, Auckland.

curated by Balamohan Shingade

What is the intimacy we must develop to create a community? What is the distance we must maintain to retain our solitude?

For his 1976–77 lecture course How to Live Together, Roland Barthes borrows a concept from monastic traditions to study forms of communal life. The word idiorrhythmy, which is composed of idios and rhuthmos, ‘one’s own rhythm’, refers to the lifestyles of monastics who live alone but are dependent on a monastery; it is a type of sociability that respects differing rhythms, temperaments and needs. In his course, Barthes opens idiorrhythmy outward from the field of religion to other everyday spaces that “attempt to reconcile collective life with individual life, the independence of the subject with the sociability of the group,” community and solitude.

Let us inhabit How to Live Together as an ongoing enquiry, and this exhibition as a scene or a course guided by the coupled question: What is the intimacy we must develop to create a community? What is the distance we must maintain to retain our solitude?

https://stpaulst.aut.ac.nz/exhibitions/past-exhibitions/2019/how-to-live-together

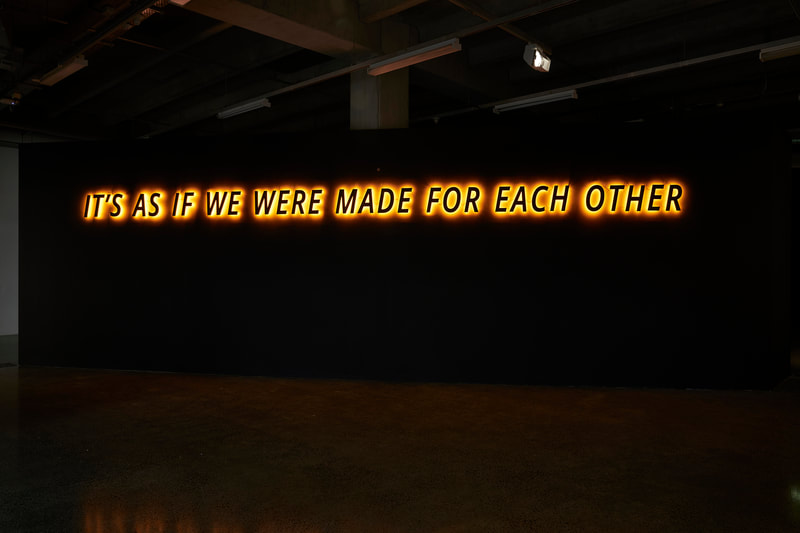

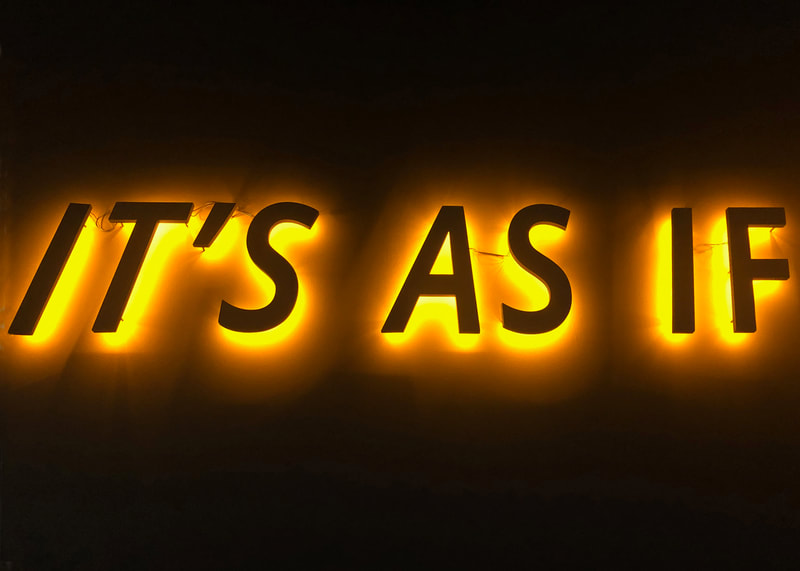

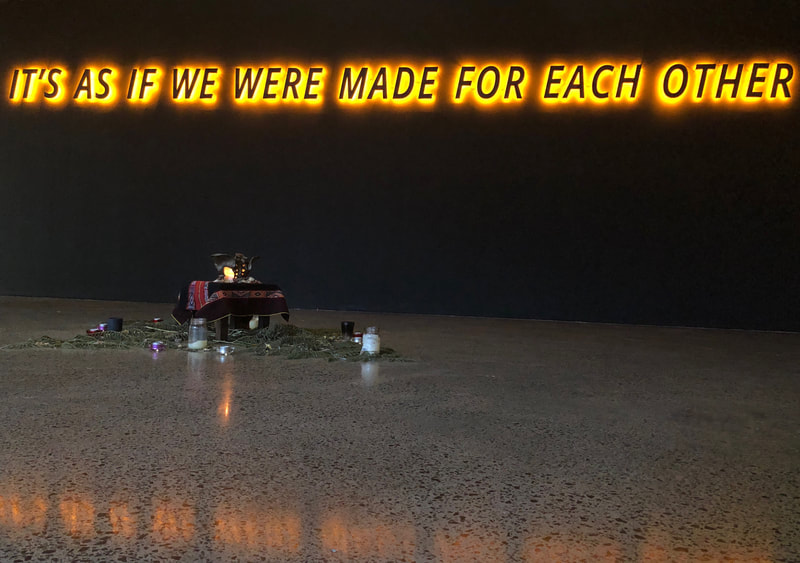

Deborah Rundle

Made for Each Other, 2019

MDF, paint, LED lights, electrical wires, transformers, 9 metres x 340mm.

Aristotle supposedly said of love, it is composed of a single soul inhabiting two bodies. Perhaps this is the origin of the romantic cliché, ‘it’s as if we were made for each other’, which Deborah Rundle utilises in her artwork. The text is large and slightly sloping across the central wall of the gallery. As a back-lit sign, it glows moodily, the colour of candlelight in a darkened room or the tungsten hue of old street lights. The phrase suggests a preordained relationship between two people, like the fateful mutualism of a flower and a bee, clownfish and sea anemones, you and me. But in the context of How to Live Together, who ‘we’ refers to is unsettled. Here, it seeks an alternative interpretation. It extends outward from the couple to a larger sense of connectedness. It implicates the viewers, and in our physical experience of the artwork, it brings the phrase into the body and the self, allowing it to work continually in our memories. When we experience the various forms of ‘coming into relationship with’ others in the exhibition and its projects, the phrase encourages reflection on community expanding out from our identities—a sense of belonging and commitment working across our differences.

For his 1976–77 lecture course How to Live Together, Roland Barthes borrows a concept from monastic traditions to study forms of communal life. The word idiorrhythmy, which is composed of idios and rhuthmos, ‘one’s own rhythm’, refers to the lifestyles of monastics who live alone but are dependent on a monastery; it is a type of sociability that respects differing rhythms, temperaments and needs. In his course, Barthes opens idiorrhythmy outward from the field of religion to other everyday spaces that “attempt to reconcile collective life with individual life, the independence of the subject with the sociability of the group,” community and solitude.

Let us inhabit How to Live Together as an ongoing enquiry, and this exhibition as a scene or a course guided by the coupled question: What is the intimacy we must develop to create a community? What is the distance we must maintain to retain our solitude?

https://stpaulst.aut.ac.nz/exhibitions/past-exhibitions/2019/how-to-live-together

Deborah Rundle

Made for Each Other, 2019

MDF, paint, LED lights, electrical wires, transformers, 9 metres x 340mm.

Aristotle supposedly said of love, it is composed of a single soul inhabiting two bodies. Perhaps this is the origin of the romantic cliché, ‘it’s as if we were made for each other’, which Deborah Rundle utilises in her artwork. The text is large and slightly sloping across the central wall of the gallery. As a back-lit sign, it glows moodily, the colour of candlelight in a darkened room or the tungsten hue of old street lights. The phrase suggests a preordained relationship between two people, like the fateful mutualism of a flower and a bee, clownfish and sea anemones, you and me. But in the context of How to Live Together, who ‘we’ refers to is unsettled. Here, it seeks an alternative interpretation. It extends outward from the couple to a larger sense of connectedness. It implicates the viewers, and in our physical experience of the artwork, it brings the phrase into the body and the self, allowing it to work continually in our memories. When we experience the various forms of ‘coming into relationship with’ others in the exhibition and its projects, the phrase encourages reflection on community expanding out from our identities—a sense of belonging and commitment working across our differences.