In the Anthropocene

Bartley and Co Gallery, Wellington.

Artists: Conor Clarke, Anne Noble, Deborah Rundle

What does it mean to make art in the age of the Anthropocene? This is the term being used to describe the growing consensus that we are living in a slice of geological time defined by human impact on the environment -- from the furthest reaches of the atmosphere to the sedimentary rock beneath us. The many implications of this recognition are far-reaching, but they all return to a fundamental re-evaluation of our relationship to the world, the way we see it, and the way we see each other.

The Anthropocene is the age of climate change, depleting resources, and mass species extinction. In its current stage, it is also becoming an era of increasing populism, authoritarianism, and ethnic tribalism across the globe. These concepts are not disconnected. The way we treat the world, and the way we treat each other, are intimately linked. The work of the three artists in this exhibition question and explore the dominant paradigms that have led the world to the position it is in today. Each asks us to reassess fundamental distinctions or separations between entrenched notions of science, nature, labour, and culture that have come to define the human age.

At first glance, Conor Clarke's photographs appear like a contemporary reimagining of John Constable's picturesque cloud studies, or Luke Howard's taxonomical sketches. However, this historical, referential quality is disrupted by the realisation that they are not clouds at all, but rather billows of steam emerging from industrial towers. These images are beautiful, but it is an uncomfortable beauty. Clarke forces us to confront the visual pleasure provoked by structures that are 'so associated with global warming they have become to represent a threat'. As it switches between natural phenomenon and man-made product, the steam pulls us through a range of emotions, from aesthetic delight to environmental terror.

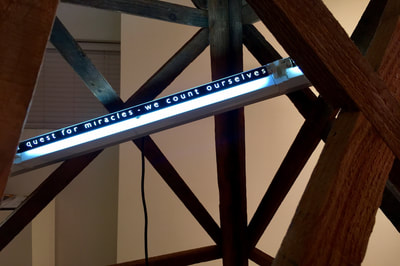

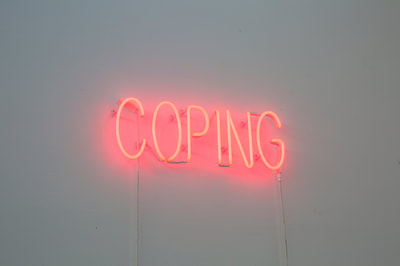

Deborah Rundle's sculptures, Spectre and Slowdown, charge the power relationships of working life with shifting meanings, buoyed by an array of historical and contemporary referents. Spectre recalls an oil derrick, a trig station, but most of all the ghost of Vladimir Tatlin's unrealised iron and glass tower, a monument to Socialist Modernity in post-revolutionary Russia. Rundle's structure is cut through by the neon lyrics of Pussy Riot's Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, contrasting the utopian dreams of Marxist revolutionaries with the contemporary realities of Putin's oppressive state. Slowdown's pink neon lettering tells us that we are COPING, or perhaps in the words of British Prime Minister, Theresa May, 'just about managing'. The work refers to a slowdown, the industrial action in which workers perform with intentionally reduced efficiency. However, it also speaks to the slowdown of economic growth and productivity, a phenomenon seen across industrialised nations since the early 2000s.

Colony collapse disorder, the phenomenon that has seen the world's bee populations drastically decline in the last century, is seen by many as a harbinger of total environmental breakdown. Anne Noble's Dead Bee Portrait #11, a scanning electron microscope image of the wings of dead bees, takes the abstract concept of the insect's extinction and converts it into a stark and confrontational reality. Blurring the distinction between art and science, Noble's bees appear as ghosts, 'haunting the present with a memory from the future'. The unbalanced ecology in which bees now live, and which we have helped to create, has contributed to the disintegration of an entire life system. Noble's work stresses the causal links between one species' fate and our own, warning that 'what is happening to the bees we are likely doing to ourselves'.

Lachlan Taylor

http://www.bartleyandcompanyart.co.nz/exhibition,Conor_Clarke,_Anne_Noble,_Deborah_Rundle,310

The Anthropocene is the age of climate change, depleting resources, and mass species extinction. In its current stage, it is also becoming an era of increasing populism, authoritarianism, and ethnic tribalism across the globe. These concepts are not disconnected. The way we treat the world, and the way we treat each other, are intimately linked. The work of the three artists in this exhibition question and explore the dominant paradigms that have led the world to the position it is in today. Each asks us to reassess fundamental distinctions or separations between entrenched notions of science, nature, labour, and culture that have come to define the human age.

At first glance, Conor Clarke's photographs appear like a contemporary reimagining of John Constable's picturesque cloud studies, or Luke Howard's taxonomical sketches. However, this historical, referential quality is disrupted by the realisation that they are not clouds at all, but rather billows of steam emerging from industrial towers. These images are beautiful, but it is an uncomfortable beauty. Clarke forces us to confront the visual pleasure provoked by structures that are 'so associated with global warming they have become to represent a threat'. As it switches between natural phenomenon and man-made product, the steam pulls us through a range of emotions, from aesthetic delight to environmental terror.

Deborah Rundle's sculptures, Spectre and Slowdown, charge the power relationships of working life with shifting meanings, buoyed by an array of historical and contemporary referents. Spectre recalls an oil derrick, a trig station, but most of all the ghost of Vladimir Tatlin's unrealised iron and glass tower, a monument to Socialist Modernity in post-revolutionary Russia. Rundle's structure is cut through by the neon lyrics of Pussy Riot's Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, contrasting the utopian dreams of Marxist revolutionaries with the contemporary realities of Putin's oppressive state. Slowdown's pink neon lettering tells us that we are COPING, or perhaps in the words of British Prime Minister, Theresa May, 'just about managing'. The work refers to a slowdown, the industrial action in which workers perform with intentionally reduced efficiency. However, it also speaks to the slowdown of economic growth and productivity, a phenomenon seen across industrialised nations since the early 2000s.

Colony collapse disorder, the phenomenon that has seen the world's bee populations drastically decline in the last century, is seen by many as a harbinger of total environmental breakdown. Anne Noble's Dead Bee Portrait #11, a scanning electron microscope image of the wings of dead bees, takes the abstract concept of the insect's extinction and converts it into a stark and confrontational reality. Blurring the distinction between art and science, Noble's bees appear as ghosts, 'haunting the present with a memory from the future'. The unbalanced ecology in which bees now live, and which we have helped to create, has contributed to the disintegration of an entire life system. Noble's work stresses the causal links between one species' fate and our own, warning that 'what is happening to the bees we are likely doing to ourselves'.

Lachlan Taylor

http://www.bartleyandcompanyart.co.nz/exhibition,Conor_Clarke,_Anne_Noble,_Deborah_Rundle,310